“Sustainability” vs “ESG”

Once upon a time, I began presentations on sustainability-related topics with a snorkel in the terminology swamp. I’d compare and contrast about a dozen terms in the “sustainability” alphabet soup – CSR, SDGs, CR, 3BL, 3Ps, 3Es, etc. Then I’d declare that they were all close enough to be synonyms for “sustainability” and move on. After a while, I stopped doing that. Now, I find it necessary to do it again, primarily to clarify “sustainability” vs. “ESG” usage these days.

Inside-Out / Sustainability

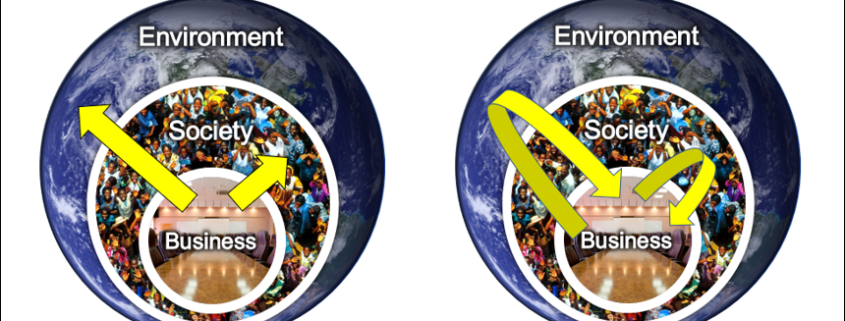

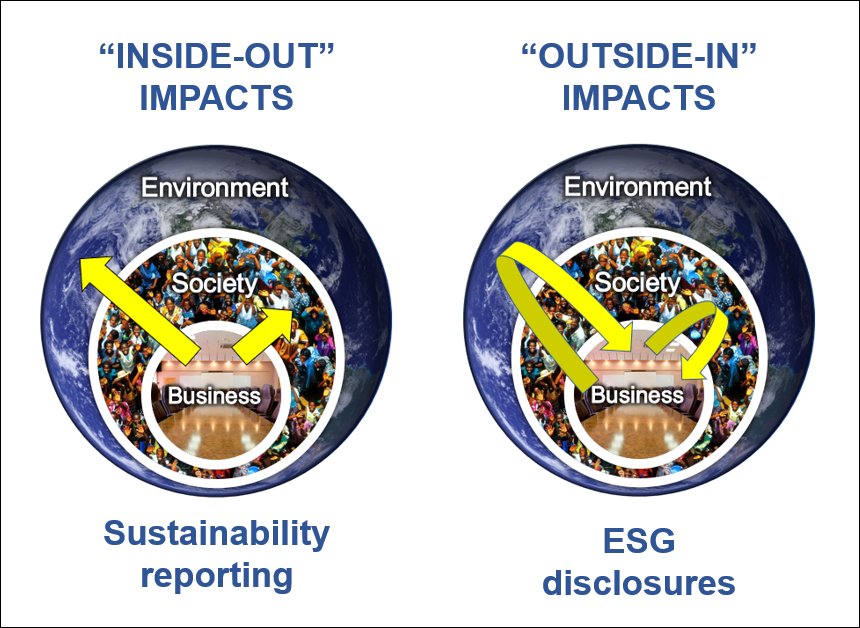

In the beginning, sustainability champions focused on trying to convince companies to cause less harm to society and the environment. We wanted them to stop polluting, treat their employees better, and help build communities – to be more sustainable. Then, we wanted them to be net positive – to not only cause less harm, but also be restorative and regenerative. “Sustainability” reporting informs stakeholders about the organization’s inside-out impacts – its positive and negative impacts on people and planet. Inside-out sustainability reporting frameworks include the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the Future-Fit Business Benchmark, the B Corp B Impact Assessment, and the Basic Sustainability Assessment Tool.

Outside-In / ESG

Then, ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) entered the lexicon. As first, it was a synonym for sustainability. The G helped legitimize sustainability as a business issue worthy of boardroom and C-suite attention. Then the financial community morphed the ESG noun into an adjective for risks. What lenders and investors wanted to know was whether a company was at risk from environmental and social impacts on the business. If so, they would be more cautious about providing capital to a risky company.

What ESG risks should concern capital providers the most? The annual Global Risks report by the World Economic Forum provides that guidance. It examines about two dozen risks that could do damage to economies / businesses within the next ten years. It classifies the risks into five categories: Technological, Geopolitical, Economic, Environmental, and Societal. Since 2016, the risk with the highest impact and highest probability of happening with the ten-year timeframe has been in the Environmental category: “Climate Action Failure.”

That led to the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) recommending voluntary climate-related financial disclosures that provide decision-useful information to lenders, insurers, and investors so that they can evaluate their risks and exposures over the short, medium, and long-term. That is, they need to understand how climate-related risks and opportunities are likely to materially impact an organization’s future financial position as reflected in its income statement, cash flow statement, and balance sheet. This is the epitome of an outside-in ESG risks disclosure.

Given this distinction between sustainability and ESG, many were understandably confused when the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) was launched last November. Its mandate is to develop a comprehensive global baseline of high-quality disclosure standards to meet investors’ information needs regarding outside-in ESG risks, starting with climate change-related risks. Perhaps “International ESG Disclosure Standards Board” (IEDSB) would be a more appropriate name for the ISSB.

Double materiality

Inside-out and outside-in perspectives are complementary. Both are material to the company. Hence, the “double materiality” label coined by the EU Non-Financial Reporting Directive. The impacts of the company on the environment and society may over time become material in investors’ eyes and require disclosure in the company’s financials. Further, the impacts of the environment and society on the company may become material in investors’ eyes and also require disclosure in the company’s financial statements. Materiality, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder.

I credit Alan Willis, a CPA Ontario Fellow and corporate reporting guru, with first enlightening me on the inside-out / outward-looking and outside-in / inward-looking classifications of assessment frameworks. His unpublished paper delivered as a keynote speech at the EMAN/CSEAR Conference last year, and our subsequent email exchanges, helped me “get it” on the two categories of assessment frameworks and the materiality of both. Outward-looking “sustainability” reports and inward-looking “ESG” disclosures are fine when the labels are used appropriately. It’s when they aren’t that we need to clarify their intended meanings.

Comments are closed.